Picture: Crescent Moon in evening light over oak tree on Palassou Ridge, Santa Clara County, California

I have to wonder, from a business perspective, if many of my older images which I shot on professional-grade transparency slide film aren’t, for lack of a better term, ‘dead’?

Earlier this spring I received a call from a client looking for images of rural Santa Clara County. I had images, but it would to take some time for me to get them online for review. You see, these images were all shot on transparency film. They are part of my stock files from back in the day when professional photographers used to send slides to clients, who would then review submissions on a lightbox using a loupe. (I refer to this as the period when photography was tangible.)

Currently a full a decade into the digital-era, sending slides to a client just doesn’t happen anymore. I honestly can’t remember the last time I sent slides to a client; perhaps now akin to listening to my last music cassette tape. To get these images to the client for review required me to edit my collection of transparencies, scan the slides, clean the scans of any dust spots, and finally post low-resolution scans online for the client to review.

Now this client notwithstanding, I have a large number of images in my files which have never been scanned at high resolution. After working through this collection of images, I’m left asking myself a larger business related question; (professionally) is it even worth the time it takes to scan and keyword these images for stock sales or distribution to stock agents?

Picture: Sunset light on oak trees and hills above Anderson Lake, Santa Clara County, California

Normally when I process a collection of images which will be put up for sale via my stock agencies or in my own image archive, I tend to work in batches containing anywhere between 75-300 images. For these rural Santa Clara images, I scanned a collection of about 70 images in total. Scanning, processing, cleaning, and captioning took the better part of a couple days work. By the time I’m done keywording the, I’ll likely invest another full day. That’s three day’s time putting effort into feeding an industry of diminishing returns, namely stock photography. In business, where time is money, this is certainly becoming more and more of a losing investment.

Worse is this same progression into the digital era means there is an ever-growing population of creative professionals working as art directors and photo editors who’ve never really seen or worked with film or film-based images. Even at one of my stock agencies, perfectly ‘sharp’ scans of transparencies which had been previously accepted without any problem are now routinely being rejected as ‘soft or lacking focus’. In a world of high-grade digital images, I can’t argue the point that film grain makes an image, on close inspection, not as sharp as its digital counterpart. So rather than have my uploading privileges completely revoked, my only other option is to no longer try and submit any images shot on slide film. These are the same images shot on transparencies which have been feeding publications for decades. Yet now they seem to be invalidated; relegated to the world of the ‘antique’. In other words, from an industry perspective, if you can’t submit them, you can’t sell them. Therefore they’ve become practically worthless.

Picture: Spring in the San Antonio Valley, Santa Clara County, California

What is a photographer to do if you have hundreds or thousands of slides which have never been scanned? For myself and many of my peers, these could represent a decade or more of photographic creativity. Do they just spend the rest of their existence locked in a dark filing cabinet? Is it worth taking the time to scan them anymore? If the answer is no, aren’t they really just being moved one step closer to the garbage can? I know for myself, that’s certainly not the ending I’d like to see for many of my older images.

Here lies the great divide, an artist who still wants to keep his images alive, viable, and seen, versus an industry and business cost calculatiosn which basically declares the images dead. For those images which haven’t yet been scanned, are they to remain forever unseen?

For myself, I both know the answer, and don’t know the answer. The professional in me says move forward, numbers don’t lie, don’t look back, yada, yada, yada. The photographer in me says these are still great images. I want them to be seen. They are valuable to me.

Do you think these images, and others like them are now worthless, and should remain tucked away in a dark and lifeless filing cabinet even if professionally it may not be worth the time and effort to scan them and bring them back to life?

I value your thoughts, comments, and any similar experiences you’d like to share on this.

Here are a few more industry-worthless(?) images:

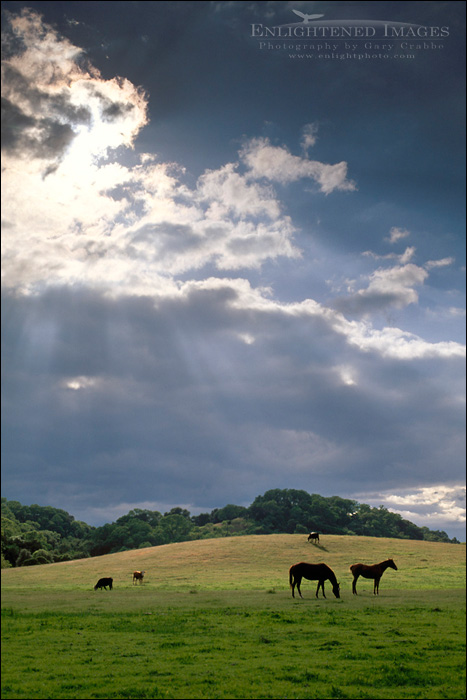

Picture: Storm clouds sand sunbeam rays in blue sky over horses in green grass spring pasture on ranch in Santa Clara County, California

Picture: Snow storm in spring dusting green rolling hills of rural Santa Clara County, California

Picture: Sunset light over oak trees and hills above Otis Canyon, from Palassou Ridge, Santa Clara County, California

Picture: Sunset light on oak trees and hills above Anderson Lake, Santa Clara County, California

—

![]()

If you like this post , I would greatly appreciate it if you’d consider sharing this with your friends using one of the Social Media sharing buttons located at the top of this post. You can also sign up to receive free updates by email when future posts are made to this blog.

![]()

—

![]()

—

Gary Crabbe is an award-winning commercial and editorial outdoor travel photographer and author based out of the San Francisco Bay Area, California. He has seven published books on California to his credit, including “Photographing California; v1-North”, which won the prestigious 2013 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Gold Medal award as Best Regional title. His client and publication credits include the National Geographic Society, the New York Times, Forbes Magazine, TIME, The North Face, Subaru, L.L. Bean, Victoria’s Secret, Sunset Magazine, The Nature Conservancy, and many more. Gary is also a photography instructor and consultant, offering both public and private photo workshops. He also works occasionally a professional freelance Photo Editor.

I know the feeling Gary! There are plenty of film images in my archive that would hold their own next to digital images shot last week, but having them scanned, keyworded and lightbox ready is another story.

My feeling is process the cream of the crop and let future requests (as you have done) dictate which images get processed moving forward.

Cheers,

Russ

I have a few hundred 35mm slides sitting in my closet. A long time ago I scanned the ones I felt were best and I have those in my LR catalogs. The rest…eh, they’re just sitting there, which is what they will probably always do. I think you hit the nail on the head: is it really worth your time investment? In my experience, the answer is “no.” Of course, your and Russ’ experience may be different.

It sucks from a business perspective Gary but if these images are representative of what you’ve left to scan then I’d say it is worth the effort to scan at least the best of the bunch. Beautiful stuff!

I’m in the same boat. There are a few images I have on slides that I could never throw out, but really the vast majority should hit the trash can – it would free up some valuable space in our house, I just haven’t gotten to the point that I can just throw away so many years of work.

If you license/sell from your own site, I don’t see any problems with 35mm scans. Some of those images continue to sell. They look fabulous on the web, and based on my experience, I’d say client complaints about IQ are very unlikely for most projects. When I sense that IQ may be a problem (typically large repro) I warn that this will have the “retro” look of film, including grain. Of course, images shot on larger format film rival the best of MFD. The main reasons I do not scan my film archive more extensively is I’ve gotten out most of the good stuff w/ 10,000+ scans and I’ve quite a digital backlog.

The way I look at it is that you have to think about more than just the commercial viability of the work. If the work is part of your life’s work and formed who you are as a photographer, then it’s worth making them part of your digital collection just for you. Of course, that’s quite a time investment though. It would be like a “personal project” that you do for you and not for selling.

It’s funny I was just thinking about doing some scanning of my old work this morning, and then happened upon a tweet of this post. It must be a sign 🙂 I know I would be devastated to loose the street photography I did in Russia over 20 years ago since it is part of who I am as a person and as a photographer. So I better get scanning!

Pardon the moment of Zen. Things change; they have to. I hate to say it because it represents a big part of your life and your art, but it may be more cost effective to shoot the locations again. Maybe this is an opportunity?

If you can’t sell them to art directors, sell them to people who will buy them via gallery and direct sales of prints to the public. Each scan you prepare can be printed and sold many times over, making the time spent preparing each image worth your while.

Hi Gary, I am an avid Amateur photographer–have been for 30+ years. I also have moved 12 times, including 3500 miles over the ocean as well as to a Central American country, before coming back to the US. We could only take what fit in a suitcase; to say it felt like ripping my heart out to throw out 23 years of my pics and art is an understatement. I still think longingly of a few of the shots I had gotten that were once in a lifetime. However, time goes on and I discovered that at least with digital, I can keep the last 10 years worth, watching the improvements in my cameras and technique. I carry within a storehouse of shots and experiences which impact every photo I take today. Since I am not a pro, I look at it from the emotional (and occasionally rational) perspective whereby those images represent not only your life but what the planet looked like then, what the film industry wanted and are therefore, history. Only you can decide if it is worth it; however, once they are gone, there is no choice, so sometimes it is worth hanging on for a while longer and seeing what you think in another 2 or 3 years.

BTW-having followed your work for a few years, I love your focus on nature, both the old ones and the current. Thanks for sharing such beauty so often.

A few years ago my retired father decided he needed to do something about his 1,000 plus slides of all the pictures he had taken (non professional) because he realized some of the oldest ones were slowly degrading, even though he has stored them carefully all these years. His younger brother and we all suggested he buy a computer, scanner, etc. and take on as a project scanning all these slides into disk format to preserve them. He did, and it took almost two years (not doing it every day) and sent the disks to my sister who keeps them for family viewing. No more slide shows for the Morgan family. He also labeled most. He has multiple pictures of some of our relatives I have never met. This is a personal family treasure, and I thank him for doing the task.

This is a sad thing to hear as your images are simply beautiful and as a retoucher i’d find it rare that they would be printed to such a size and quality to notice the “softness” that film may be perceived to have. Perhaps the stock agencies should put a tag or special symbol on images that are from film so as the purchaser knows its a film based image. If its being printed full page the softness / grain would never be seen. Perhaps its an education thing that needs to be relearned at the stock agencies? Reviewers that they have from my past experience seem to be worthless. You could send an image and it get rejected for too much grain, reupload it again and it get accepted. Perhaps its best to avoid stock agencies as an industry and only self host your libraries. The stock agencies are killing the industry and if photographers took back their images, getty and corbis would crumble and agencies would be left with one choice. Lean the creatives in the industry, develop relationships and make purchases direct. Corbis and Getty are the ones killing the industry (that and pop up photos, which will take care of itself). Photographers should really take back the power.

I experienced the same thing recently pulling a submission together for a magazine article. It was a tight deadline, and I could have doubled the amount of images submitted that fit the want list if I included what I have on film. But when I thought about the time it would take for me to get those slides digital ready, and the payment range for the article, it just wasn’t worth it.

Are they dead? I would say as a business asset, only if there isn’t an economical way to get them digitized. I haven’t looked into any services in years, I wonder if they are still around? It is such tedious work, seems it would be hard to find a low cost service. Maybe you need an intern? 🙂

Gary, welcome to my entire life representing my father’s historically significant photographs. This is why I don’t continue to do stock photography, at least with Dad’s images so far, except through the occasional direct request. Fortunately, most of his collection is either large format 4×5, 5×7 and 8×10, or medium format 2 1/4. What few 35 mm he made that were top notch, we have somehow cleaned up and restored nearly as good as digital. Not sure how you do that, as I had Carr Clifton do most of that part of it back then. He only just switched to digital capture himself three years ago. Before that he was having WCI make drum scans of his 2 1/4. Like Dad, he fortunately did not use a 35 mm camera for the work he wanted to sell. Drum scans are expensive, but usually eliminate most of the grain of the 35 mm. I have spent tens of thousands of dollars and thousands of hours on scanning and the rest of the process. I thought all photography was this hard, until I started doing my own. So… the answer is, if you have tons of money, it isn’t a problem, but I never had that much to begin with and the rest of it ran out pretty quickly doing photography. Drum or Imacon scans are the opposite of what you describe compared to digital images. Scans from large and medium format film have much higher fidelity, detail, tones, range and many other factors that still make them superior to nearly all digital capture, unless you have a $75,000 medium format digital camera. For you I would say, scan a few at a time in descending quality order starting with the very best.

Gary, my somewhat analytical view is that first, the choice is between putting in the time to move your film images to digital or putting in the (probably more significant amount of) time to reshoot the image in digital. From my perspective, if that were the only consideration, then spending time to bring perfectly good (and in your case, excellent) film images into digital form is a no-brainer.

But from what you’ve said, the stock agencies will not accept these “too soft” images. I’d suggest it is not worth jeopardizing your reputation and standing with them by submitting images you know they won’t accept. And I can certainly understand your feeling about these photos and what they represent in terms of your career and your body of work.

I’d suggest that still leaves you with the option to continue to offer them as individual prints for sale. And, as an artist (oh, I know you don’t like to think of yourself as one but my bet is most of your admirers believe that the shoe fits) I believe it is important for you to retain the collection in some usable form for the future (I’m speaking about posterity here).

It’s a tough call, but you need to base it on economics – not your heart.

If you can reasonably identify the ones worth considering, it sounds like a great job for an intern. You’re not looking for perfection – just get them scanned and keyworded. It’s not free – but it’s a lot cheaper than your time and effort. Consider someone through the NANPA scholarship program – someone already vetted and committed to photography.

In order to monetize them, how about microstock? The images obviously have merit but probably don’t fit traditional stock work of today. Send them through a stock channel you are not using and see what happens.

My guess is its tough to make the economics work if you invest your time and effort in these images. Most won’t have enough value to justify a big project. You could do it piecemeal as you get requests from clients, but unless you are making money on the images you’re just adding cost.